By Mohammed Barber

“What honour is left to us, when we have to take orders from a handful of traders who have not yet learned to wash their bottoms?”

Narayan Singh, a Mughal officer

70 years ago this year, two of the twentieth century’s most important events took place: the Independence and Partition of the Indian Subcontinent. Not only did a British colony gain independence, but a line was drawn through it, dividing it into two separate nation-states along “religious” lines: India and Pakistan, events that are still acutely felt between the peoples of both countries today.

And yet, not only is it that too few know of these important events, but what is known is often misunderstood.

The next few months will, then, trace the tense history of Indian Independence and Partition in a series of articles.

The topic of this article: how did the British come to rule India?

“There are more Mughal artefacts stacked in this private house in the Welsh countryside than are on display at any one place in India – even the National Museum in Delhi.” William Dalrymple.

The East India Company

India has often been called the “jewel” in Britain’s Empire, perhaps because in the early 1700s the Mughal Empire was one of the world’s wealthiest polities owning 25% of the world’s wealth. Coupled with a massive population, which meant a huge workforce, India was a fertile land to exploit.

This exploitation did not occur, in beginning, directly by the British government, but through a private corporation: the East India Company.

Born on New Year’s Eve 1600, The East India Company (EIC) was given a fifteen year monopoly for “trade to the East” by Elizabeth I. Permission to “to wage war” where necessary came as an added bonus.

The company first landed in Surat, Gujarat, in 1608, and in the subsequent decades established themselves in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. European demand for Indian goods – pepper, spices, textiles – turned these cities into huge exporters, particularly Calcutta which amounted to half of all EIC exports.

Exports brought in huge revenues which meant the EIC could offer military services – by hiring Indians known as sepoys – to local Indian rulers, who were only too happy to accept as it gave them the upper hand in their internal politics. In return for military services, the rulers offered land and trading rights. As a result Bombay was virtually “owned” by the company.

The Battle of Plassey 1757 and Company Rule

But the big turning point came in 1757. In the year before the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-daulah, marched on Calcutta taking it from the company. There was an uproar back in Britain over this: how could the white British be defeated by the racially “inferior” Bengali? This was typical colonialist thinking of the age, compounded further by exaggerated reports of British soldiers suffocating to death in their prison cell. So a military force set sail from Madras to retake the city. Moreover, as Bengal was immensely rich, the company wanted/needed it back.

Colonel Richard Clive, described by historian William Dalrymple as an “unstable sociopath”, led the force, and upon reaching conspired with merchant bankers and Siraj-ud-duala’s army general, Mir Jaffar.

Colonel Richard Clive, described by historian William Dalrymple as an “unstable sociopath”, led the force, and upon reaching conspired with merchant bankers and Siraj-ud-duala’s army general, Mir Jaffar.

The Nawab’s soldiers were bribed to throw away their weapons, surrender early and even turn against their own army. Therefore despite the Nawab having a much larger army, he lost the battle. Jaffar was installed as the puppet Nawab of Bengal by the EIC, and so began in 1757 the century of “company rule”.

Money flowed in from Bengal providing the finances to expand colonial control into the rest of India through “military despotism”, to quote historians Ayesha Jalal and Sugata Bose.

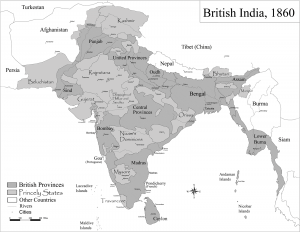

Some Indian rulers and tribes people did, however, fight back. Tipu Sultan of Mysore and the Maratha warrior lords arguably presented the greatest threat, but were defeated in 1799 and 1812 respectively. By this point the company had direct control over most of the Indian subcontinent, and indirect control over the rest.

“What honour is left to us?” asked a Mughal official named Narayan Singh, shortly after 1765, “when we have to take orders from a handful of traders who have not yet learned to wash their bottoms?”

All the while, Indians were employed by the British in administration and the army. As the EIC expanded their operations across India, so did the use of sepoys growing rapidly in size, from 100,000 soldiers in 1789, to 155,000 during the Napoleonic wars and perhaps as large as 260,000. This made what was effectively a mercenary force – the company’s private army – one of the largest European style standing armies in the world. In other words, the EIC used the Indians to colonise India.

It’s important to emphasise the significance of what the East India Company had achieved by the turn of the century, chiefly that a private corporation, with its own private army, had colonised an entire country.

The Great Mutiny/Indian Uprising 1857

The next great change in Indian rule came after the Great Mutiny/Indian Uprising in 1857. It was sparked by the lubricant used to grease rifle cartridges, made out of pig and cow fat, which didn’t sit well with the Muslim and Hindu soldiers. But the decades that led to 1857 were characterised by deposing Indian aristocrats, economic depression, heavy taxes and having next to little regard for the people the EIC ruled. As a result, discontent has been simmering away for years.

The rebellion was largely confined to central and northern India. Though there had been rebellions before, the almost spontaneous and soldier/civilian/aristocratic mix singles 1857 out. This was the greatest rebellion the company ever faced, and was crushed with inhumane animosity, to put it mildly.

Places of worship were confiscated and in some cases destroyed, summary

hangings with corpses put on public display, houses razed to the ground to make way for canals and roads are only some of the punishments Indians had to endure for rebelling against their colonisers.

In the end, it was the British government who ended “company rule”. Criticism of the EIC’s corruption, among other things, had been mounting for years. So, it was nationalised the following year, limping on until 1874 when it was finally dissolved.

The British government now had control over India, a one way relationship that would continue to bring material and strategic value to the British Empire. This is perhaps the main reason why the British wanted India, and fought so hard to keep it throughout its rule for the next century.

And so began the 100 year British Raj.