By Mohammed Barber

“We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect”.

Thomas Babington Macaulay’s Minute on Education in 1835

As mentioned in the first article in this series, “The British in India”, the British needed the Indians to colonise India. Part of that meant the need for educated Indians to work in administration. In that regard, educational institutions were set up to create, in the words of Thomas Babington Macaulay, “a class of persons Indian in colour and blood, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in interests.”

In the beginning, at least, the early Independence Movement was led by the newly educated Indian middle class. Ironically, then, the seeds of the independence movement were planted by the British themselves.

This article looks at how the independence movement started after the 1857 Mutiny/War of Independence leading up to the First World War.

Founding of Congress

To get a job in the coveted Indian Civil Service applicants had to pass an exam held only in England. The most senior positions in the Service were held by the British, and in any case many British officials did not deem “half educated natives” worthy due to the “insurmountable distinctions of race qualities”.

British education led to the rise of a new middle class, who seeing that the Civil Service was closed off to them, took to journalism, teaching, politics, and law instead. They also realised the need to organise themselves on a national level to extract concessions from the British. Regional organisations in Bengal, Poona, Madras and Bombay, among others, had existed since the 1870s, but they largely had the interests of the aristocracy and landed classes in mind, and not the new middle class.

In 1885, therefore, 73 of these city based professionals came together in Bombay for a national conference in late December, and called themselves the Indian National Congress.

It is important to stress that the founding of Congress was not the start of the Indian Independence Movement the simple reason this was not what the early congress leadership fought for. Instead, they wanted more Indian representation in regional legislative councils, in administration, a say in the government budget and lowing army expenditure.

One of the founding members of Congress was Dadabhai Naoroji, affectionately called the Grand Old Man of India. Born into a poor Gujarati speaking Parsi family in Bombay in 1825, he would go onto becoming an intellectual, businessman, and political activist. In 1882 he even became the first Asian to be elected into the British parliament.

Though Naoroji was part of the early Congress leadership, when he gave his second presidential address in 1906 aged 81 (his first presidency was in 1886), he gave Congress a tangible political direction when he called for swaraj, or “self-rule”.

You can find more about Dadabhai Naoroji here.

Swaraj in 1906 didn’t mean full independence from the British, but rather India would control its own affairs under the commonwealth banner, as a dominion of the British Empire, much like Australia or Canada at the time.

Nonetheless, the idea of “self rule” with dominion status was too radical for some of the early Congress leadership, and Naoroji was criticised for it. Though it was, in part, the failure of Congress to achieve anything of significance that led to calls for “self rule” in the first place.

Partition of Bengal 1905

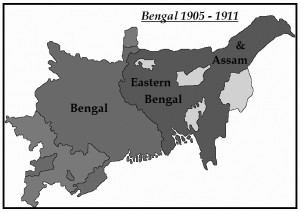

For some, the desire for a bolder approach was justified by Lord Curzon’s “aggressive imperialism”, to quote historians Ayesha Jalal and Sugata Bose. His most controversial act as Viceroy was partitioning Bengal in 1905 into two parts.

Though Curzon said the move would improve administrative efficiency, i.e. make the place easier to govern, partitioning the province was a political move. Curzon’s Home Secretary to India said, “Bengal united is a power; Bengal divided would pull in different ways…one of our main objects is to split up and thereby weaken a solid body of opponent to our rule”.

This was typical of British imperial policy, to divide India into caste and religious categories, and treat one with favour at the expense of another.

More insidiously, by creating a Muslim majority East and a Hindu majority West, Curzon pitted the two communities against each other. He claimed the Muslim East could resurrect the past glories of the Mughal Empire, a particular draw given Muslim rule in India had collapsed after 1857.

The Bengal issue fired up nationalists all across India. As Barbara and Thomas Metcalf have put it:

“Nationalists across the country took up Bengal’s cause, appalled at British arrogance, contempt for public opinion, and what appeared as blatant tactics of divide and rule. Calcutta came alive with rallies, bonfires of foreign goods, petitions, newspapers, and posters. Agitation particularly spread to the Punjab and to Bombay and Poona.”

The partitioning of Bengal marked the start of the Swadeshi (own country) movement, which involved boycotting British goods and producing artisan goods locally. But there were those who wanted to go a step further and boycott the British Indian Administration, as well as adopt revolutionary terror. The difference split Congress at the 1907 Surat conference.

All India Muslim League

Meanwhile, in 1906 a conference was held in Dacca, Bengal, organised by Muslims concerned about perpetual Hindu domination in a country where they were numerically inferior. Thus the All India Muslim League was born, and though it claimed to speak on behalf of Muslims, it would remain a largely an elitist group without popular Muslim support until WWII.

Congress eventually went back on their resolution to support the swadeshi movement and boycotts, instead preferring to tow a more moderate line. Bengal was reunited after the partition was annulled in 1911, but Congress would remain divided for another few years.

Reunification was also a blow to loyalist Muslims in Bengal, paving the way for the Muslim League to gain traction amongst the Muslims of India.

Though both the Congress and the League were headed by the new middle class, the movement to free India from direct British control, and another to express the Muslim voice had begun. The First World War, however, would take the independence movement to the masses.