By Mohammed Barber

There is nothing surprising in a Muslim or a Pathan like me subscribing to the creed of nonviolence. It is not a new creed. It was followed fourteen hundred years ago by the Prophet all the time he was in Mecca.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

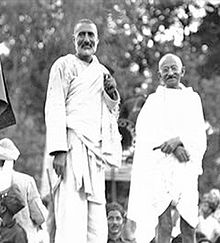

Perhaps the greatest hallmark of the Indian Independence Movement was the use of non-violence to oppose the British. Gandhi may be the most recognisable figure of non-violence in India, but he was not the only one – the Pushtuni Abdul Ghaffar Khan was another. It is to these two figures we now turn.

The first nonviolent mass protests from the early 1920s – Non Cooperation and Khilafat Movements – had largely ended in failure and were eventually called off. The economic context in which it was possible to launch these movements i.e. heavy unrest amongst the masses due to WWI, returned in the 1930s.

The world was plunged into a deep Depression in 1929, devastating the rural poor. It was on the back of this economic decline that Gandhi launched his second round of non-violent protest; the civil disobedience campaigns.

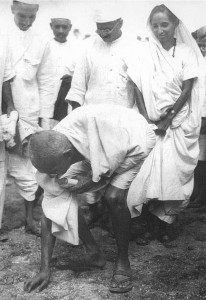

Perhaps the most famous of these campaigns was the 1930 Salt March. Gandhi needed a campaign to cut across social and caste barriers, to unite the rich and poor in the struggle for independence. He chose to focus on the oppressive British tax on Indian salt.

Starting in Ahmadabad, he marched through Anand, Bharuch, Surat, Navsari and finally finishing at Dandhi. Tens of thouands, including women for the first time, joined Gandhi in his nearly 240 mile journey. The march attracted international attention, and the world watched as this frail looking man in a “lunghi” defy the Great British Empire. Gandhi sharply highlighted British oppression in India to the world, forcing the British to negotiate.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan

A lesser known figure who advocated non-violence was the Pukhtun leader, Abdul Ghaffar Khan. He was born in 1890 into a wealthy family in the North Western Frontier Province (NWFP), in what is today Pakistan.

The NWFP acted as a buffer state between British India in the south and the Russia to the north. It therefore suffered a “particularly severe pattern of colonial exploitation and economic, political and legal injustice”, to quote historian Mukulika Banerjee.

Ruled with an iron fist, taxes and rents were “crushingly high”, state authorities given a free hand to do what they wanted, and social provisions such as schooling, hospitals and sanitation kept very poor.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan, affectionately called Badsha Khan, therefore took to opening schools throughout the 1920s. But his major achievement was creating the Khudai Khidmatgar (KK), or the Servants of God, in 1929. This was a group of about 100,000 non violent activists who set up schools and provided other social provisions throughout the province, and protested the colonialist state through non cooperation.

Though there are parallels between Badsha Khan and Gandhi programmes for non violence, the former created his programme largely independently from the latter. Whereas Gandhi’s non violence was rooted in Hinduism, Badsha Khan’s came from Islam, highlighting the virtues of patience and forgiveness stressed in the Qur’an.

British Retaliation

After giving a speech urging resistance to British rule, Badhsha Khan was arrested along with other KK leaders in 1930. His supporters took to the Qissa Khwani Bazaar in Peshawar to protest. The crowd refused to leave, so British troops emptied their magazines into the unarmed crowd, killing at least 230 and injuring over 500. Keeping to their pledge of non violence, the crowd did not retaliate and in some cases even turned to face the onslaught of bullets.

Gandhi’s Salt March forced the British to negotiate, resulting in the Gandhi-Irwin Pact and a ticket to the Second Round Table Conference where the future of India’s Constitution would be discussed. Both initiatives ultimately produced nothing of substance and Gandhi restarted his civil disobedience campaigns in 1932. The British responded by arresting over 120,000 in the next 15 months.

1935 Government of India Act

In order to stop the “Congress juggernaut”, as Barbara and Thomas Metcalf have called it, the British introduced the Government of India Act 1935.

However, instead of moving towards a British withdrawal, the 1935 Act attempted to divert Indian political attention towards the provinces, and counterbalance the Congress by including British patronised Indian Princes into an Indian Federation.

Ultimately the 1935 Act served to safeguard British rule in India, leading Nehru to describe it as “a new charter of slavery”.

Elections introduced in 1935 were contested two years later, securing major victories for Congress, winning 758/1500 seats. The Muslim League, on the other hand, failed to get a foothold even in the Muslim majority provinces, winning only 5% of the total Muslim vote. Emboldened by their victories, Congress rebuffed the League’s proposal for a coalition overlooking the fact many of those seats reserved for Muslims were won by the League across the country.

By patronising various categories, such as Indian Princes, Indian Muslims, and the “depressed classes”, the British succeeded in pitting these “categories” against one another to win power the British never intended to give away. Voting, therefore, rather than “preparing” India for democracy, became an imperial strategy to harden fluid boundaries.

This patronage would really favour the League, who managed to completely overturn their 1937 electoral defeat during the course of the Second World War.